Often in the longer structures like bridges, you will see that there are thin gaps intentionally placed in the long structural members. These are called concrete joints, and they are very useful in preserving the concrete over long time. Today, we will take on the what, why and how's of concrete joints.

Concrete has immense compressive strength, but not much tensile strength. Which is the primary reason we provide reinforcements inside concrete. However, some structural members, or some parts of them have to be made without reinforcement. What happens when these come under unexpected tensile stress?

One of the reasons of unexpected tensile strength is that concrete undergoes shrinkage over time. This creates tensile stress inside the member automatically which is hard to foresee. Now, if the tensile force being generated over time is gradually rises above the member's tensile strength, then it will, eventually, crack the concrete. Which, as you can expect, may have disastrous effects.

This is exactly why concrete joints are needed. Joints are provided in concrete in order to prohibit, or, at least minimize the possibility of cracks appearing automatically due to shrinkage from time or temperature changes.

One can say, joints in concrete are pre-planned cracks. They are created at portions where there the concrete is expected to undergo tension most, regulating the tensile forces there and pre-empting the formation of cracks.

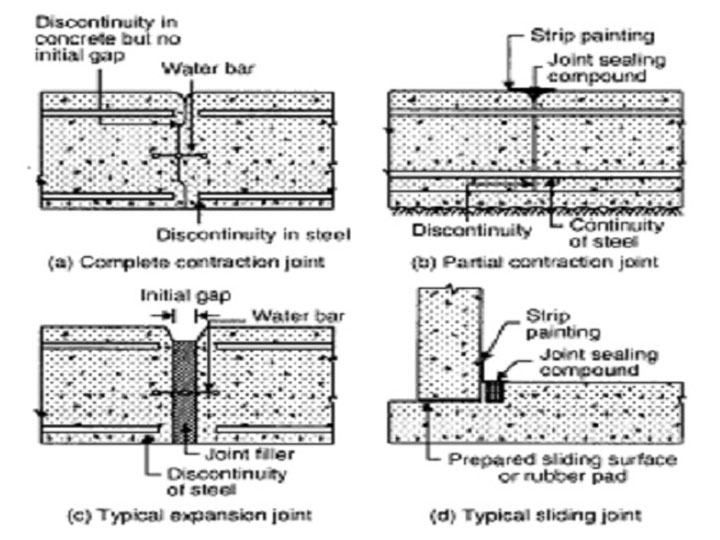

There are four kinds of joints provided in concrete slabs or pavements depending upon the need or the expected scenario. They are as follows:

Now let us see about each type of concrete joint in detail.

When you already have a pre-existing joint network running along the system, placing a construction joint makes the most sense. They are placed in a concrete slab to define the extent of the individual placements.

A construction joint is created in such a way that it will allow displacement between both sides of the slab, but will also transfer flexural stresses on the member coming from outside. It should let displacements happen perpendicular to the surface of the joint. This is the movement caused by heat and shrinkage related tension.

However, they must not allow any movement vertically, or worst of all, they must not allow any rotational displacement. Because that would defeat the whole purpose of the slab being there.

When we have to worry about not only the length of the concrete member but also the volume of it, then we use expansion joints. They are basically a small gap left intentionally by sawing, tooling, or using joint formers, which the concrete can utilize when expanding.

A contraction joint is the best example of an “intentional, man-made crack”. They are basically cut concrete in the place when cracks are expected to appear. It intentionally weakens the concrete and by so it regulates the location of the cracking caused by dimensional changes in the slab.

As you may have realized, contraction joints are the most common type of concrete joints, so “joints” in concrete generally means contraction joints unless otherwise specified explicitly. They are defined by their method of load transfer and the spacing at which they are placed.

In general, we place contraction joints at 25% to 30% depths of the concrete slab, and are spaced out at a distance of 3 to 15 meters.

Isolation joints are simply a gap given between the untrustworthy concrete and a softer member, like a pipe, a wall, a non-concrete member etc. This is mostly true for walls and columns whose footings go much deeper than the subgrade of the concrete slab. They won't displace the same way as the slab would, so you have to keep them separated.

Sometimes, if the other member beside the concrete slab or pavement is a much stronger thing, then there will be considerable resistance when the concrete tries to displace. This will end up in the slab damaging itself, instead of the other member. So, providing an isolation joint here also is a good idea.

Note that expansion or isolation joints are almost never needed indoors, because there wouldn't be that much temperature difference indoors. Also, make sure you cover up the joint area properly, or external matter-like moisture and small stones-can get into the joints and make things very ugly in the long run. Concrete blow ups are a common example of what might happen with carelessly finished concrete joints.